The Work Innovation Lab at Asana, a think tank led by Rebecca Hinds, is on a mission to help businesses understand and respond to the changing nature of work. This includes research on how managers can rethink meetings in just five steps.

Rebuilding Meetings From The Ground Up

Rebecca said: At The Work Innovation Lab, we started our research on meetings with Meeting Doomsday – a pilot study that Francesca, a community manager on the marketing team at Asana, and eight of her fellow marketing colleagues, sought to reduce the amount of time they spent in meetings.

We found that on average, each volunteer saved 11 hours per month. Francesca turned out to be our Doomsday all-star, saving 32 hours a month.

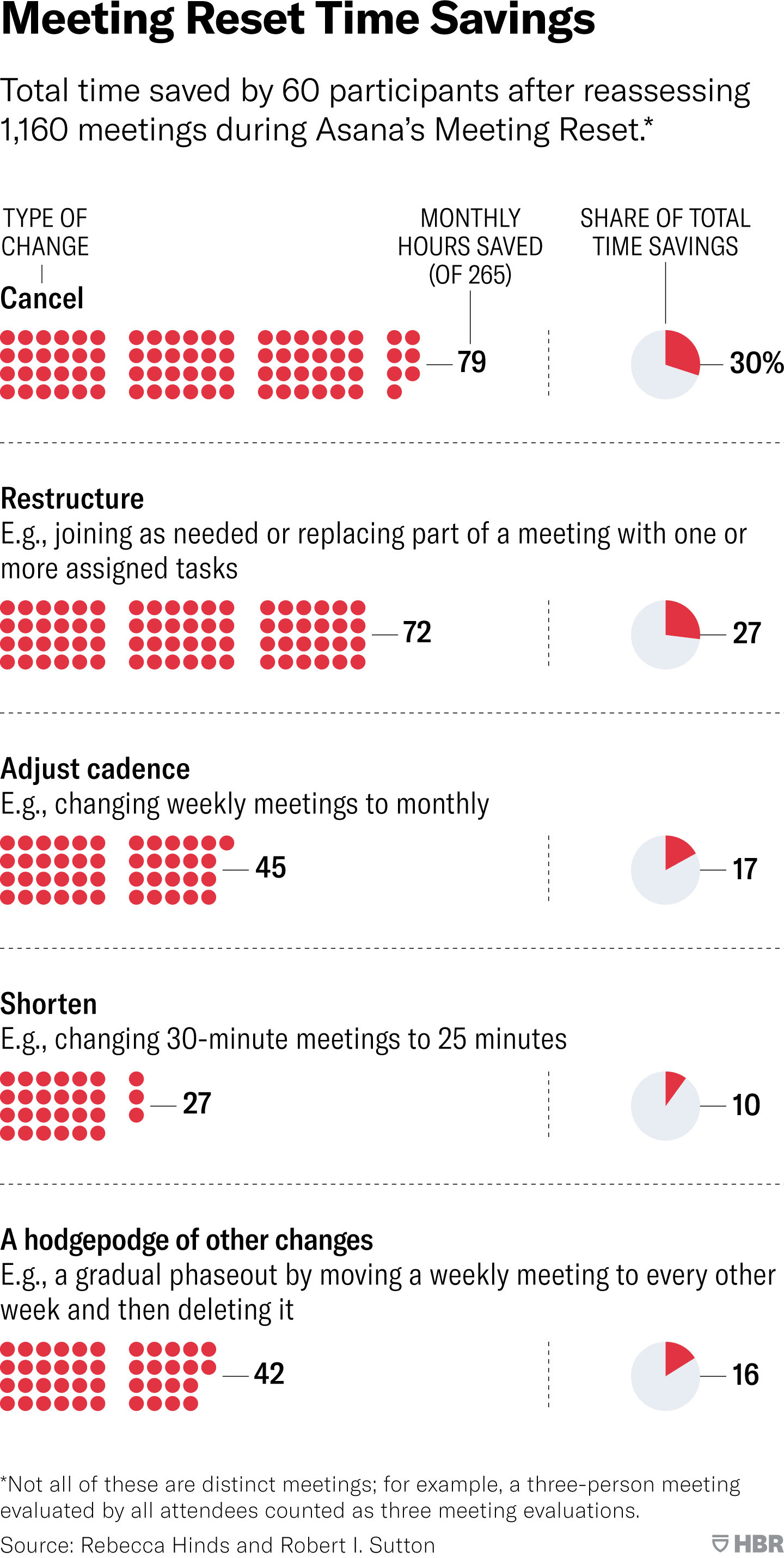

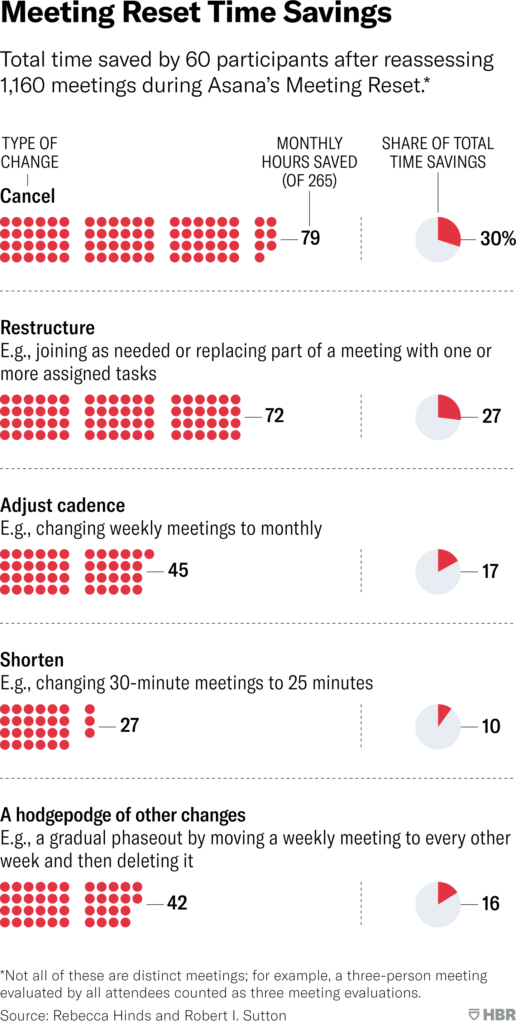

We followed up Meeting Doomsday with a “Meeting Reset,” where we studied 60 Asana employees within the marketing team and assessed 1,160 of their standing meetings. The time savings were less dramatic than Doomsday but still packed a punch. Those 60 people saved a total of 265 hours per month by eliminating and revamping meetings. We used the lessons from Doomsday and the Reset to create a Fixing Meetings Playbook to help other companies rethink their meeting cultures.

How To Fix Meetings

The Playbook contains a step-by-step guide to help you identify, eliminate, and repair broken meetings. As we analysed the results of our meeting research at The Work Innovation Lab, we identified five key ingredients for success:

1. Adopt A Subtraction Mindset

Humans’ default mode for problem-solving is to add something, rather than take something away. Through a series of studies, Gabrielle Adams of the University of Virginia and her colleagues found that “subtraction neglect” is pervasive. This “addition sickness” also plagues meetings — people keep piling more onto already chock-full calendars without much thought.

Adams’ research shows that when people are reminded to subtract and pause to do so, the interruption dislodges some of their cognitive machinery and they adopt a subtraction mindset. One way to trigger this mindset is to use simple rules, like the “rule of halves” Leidy Klotz (author of Subtract) and Robert have proposed. Imagine that all your meetings were cut by 50% along dimensions including number, length, and size. What would happen?

Doomsday activated this mindset. As volunteers repopulated their calendars, they subtracted — a lot. They removed some low-value meetings for good. They shortened and changed the cadence of others. Some 30-minute meetings became 25 minutes. Some weekly meetings became monthly.

2. Start With A Clean Slate

We invited Reset participants to join one of two groups. The first was the “full participation” or “Full Doomsday” group: They purged their calendars for 48 hours, evaluated each meeting, and then repopulated their calendars. The second group chose a “light” version: They assessed each meeting on their calendars but didn’t do the 48-hour purge.

Both groups saved time, but the Full Doomsday group saved an average of five hours per person each month versus three hours for the light group. When we asked Gabrielle Adams about this difference, she suggested the “clean slate” approach nudged volunteers to slow down and think more deeply about whether meetings were necessary or if they could be redesigned — while people in the light group didn’t slow down as much. Adams pointed to evidence in Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow, which shows people are more likely to generate new ideas and abandon old habits when they pause for deep deliberation.

Adams’ argument dovetails with reports from the Full Doomsday group. They said that they not only used the 48 hours to think about which meetings to remove and which to add back, they used the break to “cleanse” their assumptions about the design of meetings they kept.

3. Use Data To Decide What To Subtract

Both the Doomsday and the Reset were data-driven pursuits. In the early phases of each study, we crunched the numbers to show people all the time they frittered away in meetings — which convinced many to volunteer.

One lesson from the Doomsday pilot was that people sometimes struggled to assess the value of each meeting. So, we developed a simple system for the Reset. Volunteers rated each recurring meeting on two dimensions on a three-point numerical scale:

- The effort required (including prep, actual meeting time, and follow-up work) for each meeting.

- The value of each meeting for helping them reach their goals.

Participants reported that this part of the audit was especially useful because it was easy and prompted them to think about each meeting more deeply.

As a result, we built a model based on the Meeting Reset that predicted low-value meetings with over 80% accuracy. It considers factors including meeting length, size, day of the week, and title. Meetings on Mondays were rated as most valuable. Wednesday meetings, which coincided with Asana’s “No Meeting Wednesdays,” were least valuable, probably because people resented when colleagues violated the explicit company norm of not scheduling meetings on that day. In addition, meetings with titles that included specific project and team names were rated most valuable, while vague “catch ups” and “coffee chats” were least valuable.

4. Create A Movement

Meetings are easier to fix when people do it together — when it feels like a movement, be it in your team, department, or entire organisation. Unlike the Dropbox purge, neither Doomsday nor the Reset were top-down changes. Asana employees were given the choice to opt in and encouraged each other to cut and revamp meetings while sharing ideas for doing so.

As with any movement, some people were enthusiastic, others went along grudgingly, and others elected not to join. But even teammates who didn’t join still benefited because their loads got lighter, too. And some who initially resisted joining the Reset did so after they experienced and heard about the benefits from volunteers.

5. Don’t Just Subtract Meetings — Redesign Them

We were surprised by how much time savings from the Meeting Reset came from changes other than eliminating meetings completely. Only 30% of the time savings came from cancelling meetings entirely; the remaining 70% came from volunteers who redesigned the meetings they kept. For example, 27% came from restructuring meetings so that fewer people attended or from replacing parts with asynchronous communication. The leader of one low-value meeting eliminated a time-consuming ritual where each attendee shared a status update at the outset and replaced it with written updates from each on Asana and Slack software instead. Substantial time savings also came from meeting less often (17%) and shortening meetings (10%).

Clear the Way for What Matters Most

Rebecca said: We checked back with Francesca six months after Doomsday. Her calendar remains lighter. She reflected, “Philosophically, we’re sticking to the Doomsday learnings. It has left a legacy — we are revising our meetings more frequently, and adjusting meetings so that we nail the cadence and time of the week.”

As you use the Fixing Meetings Playbook and embrace the subtraction mindset, don’t try to make everything quick, easy, and frustration-free. The goal is to make time for the things in life that ought to be slow — like pausing to think about your work and taking time to take care of yourself and others. Francesca told us, “Because I have more breaks in my day, I’m able to match my energy levels to specific types of work — or rest. I can meet with people when I have enough energy to engage deeply. When my productivity dips, I have enough meeting-free time in my calendar to stretch and walk away from my laptop.”

For Francesca and her colleagues, the calendar cleanse jolted them to abandon ingrained habits and gave them more time to think about tough problems, enabled them to bring their best selves to the meetings that remained on their schedules, and helped protect them from the emotional exhaustion that results from attending too many meetings — especially bad ones.